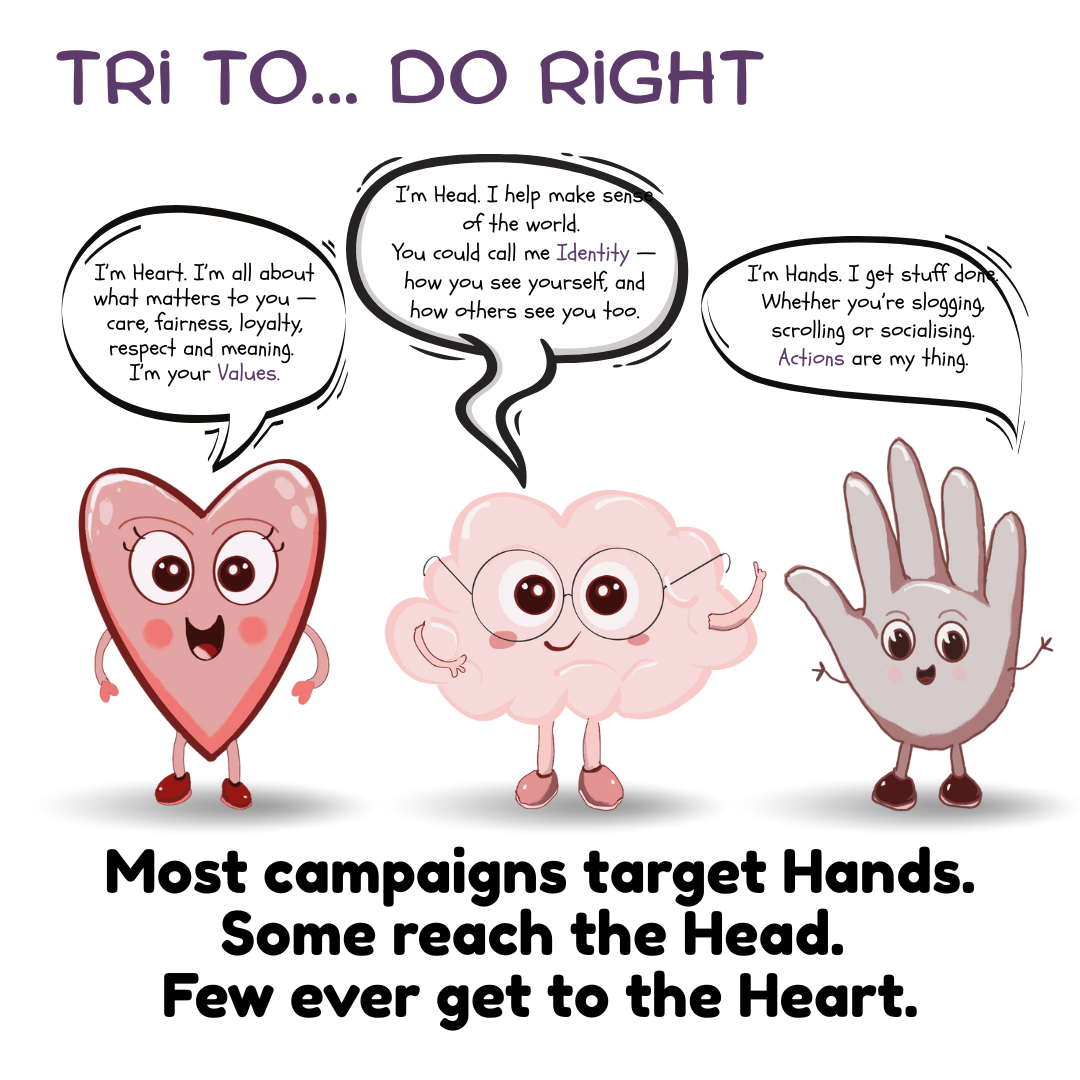

Turning Hearts, Heads and Hands: why changemakers need to target values, identity and action together.

“How do we get people to recycle more? Drive less? Switch suppliers?”

What if we’ve been spinning the wrong cog?

My PhD (100 years ago) was in behaviour change and introduced me to the world of identity theory and social norms, which shaped my subsequent career, but I didn’t go deeper – until now.

Much of the behaviour change work I’ve seen and been involved with focuses on actions, occasionally social norms but often not much deeper. Academic and anecdotal evidence suggests we need a more interconnected model — one that doesn’t just focus on what people do and why they think they do it but looking at the core beliefs that shape their thinking.

Climate change isn’t just a scientific or economic issue. It’s a psychological one.

People don’t respond to facts alone; they respond to what matters to them. That means changemakers need more than carbon footprints and policy briefings — they need a better understanding of how humans make meaning and take action.

This article explores a three-part model that brings together values, identity and behaviour into a single behavioural system. It shows why campaigns that target only action often backfire, how identity can amplify or block engagement, and why values — particularly moral foundations — offer the strongest bridge across social and political divides.

Building on work I started decades ago; I propose a model of three interlocking cogs.

The cog model: Heart, Head and Hands

We can think of human behaviour as a system of three connected drivers:

- Heart = Values

Our emotional and moral compass — what feels important, right, or meaningful - Head = Identity

How we see ourselves — our roles, affiliations and self-image - Hands = Actions

The behaviours we carry out — from how we vote, shop and travel to what we share or ignore

These aren’t linear steps. They form a dynamic feedback system:

- Values influence identity ⇄ Identity shapes behaviour.

- But actions can also shift identity and even bring latent values to the surface.

- All three are shaped by broader forces — culture, environment, upbringing, social norms, media exposure and power structures.

This isn’t a formula. It’s a set of moving parts — sometimes aligned, sometimes in tension.

Understanding this complexity helps communicators design strategies that work with human psychology, not against it.

Example: Same behaviour – different motivations:

Behaviour: Cycling to work every day

At first glance, this looks like a success for any sustainable transport initiative but scratch the surface and we find very different reasons behind the same action — each driven by distinct values and identities.

|

Person |

Value |

Identity |

Motivation |

|

A |

Environmental care |

Conscious citizen |

“I cycle to cut emissions” |

|

B |

Health |

Active individual |

“It keeps me fit” |

|

C |

Frugality |

Savvy parent |

“It’s cheaper than driving” |

|

D |

Efficiency |

Busy professional |

“It saves time” |

So what?

These people are doing the same thing, but if your campaign only speaks to one rationale — for example, “cycle to save the planet!” — it risks missing or alienating the others.

If you want more people to get on a bike, you need to:

- Speak to multiple values

- Acknowledge diverse identities

- Offer framing and messaging that allows everyone to see themselves in the story

Campaign implication - Don’t assume shared motivations, build overlapping ones. - For Person A: “Cycling reduces emissions and protects what we love.”

- For Person B: “Cycling supports your health and wellbeing.”

- For Person D: “Cycling beats traffic and gives you back your time.”

A successful behaviour change campaign doesn’t need to guess someone’s true reason — it just needs to give them a reason that feels true to them.

Example: When the cogs fall out of sync

Emma works in sustainability. She cares deeply about the planet but flew to a work conference.

- Heart (Values): “I feel guilty – flying harms the planet”

- Hands (Action): “It wasn’t feasible by train”

- Head (Identity): “I help others act on climate — this trip supports that”

Discomfort like Emma’s isn’t a sign of failure — it’s often a signal that someone cares deeply.

When campaigns ignore that inner conflict, or respond with shame, people don’t change — they withdraw.

Instead, effective communication acknowledges the tension and helps people re-centre on their identity and purpose. Not by telling them to do less, but by asking:

“Where can you add the most value?”

“How can your skills, voice or decisions help move things forward?”

This approach shifts the focus away from guilt and sacrifice, and towards agency, alignment and momentum — all three cogs working together again.

Why identity is the hinge

Identity is the internal story of who we are — our roles, affiliations and sense of self. Research tells us that identity alignment with environmentalism (seeing themselves as the type of person that cares about the environment) predicted behaviour better than knowledge – so put your stats and focus on the relatable stories.

Not all values are equal — or equally shared

One of the major reasons climate campaigns fail is that they often appeal to only one type of value — usually fairness or justice - but values vary across cultures and ideologies.

Moral Foundations Theory (Haidt & Graham, 2009) suggests five core values:

- Care / Harm

- Fairness / Cheating

- Loyalty / Betrayal

- Authority / Subversion

- Sanctity / Degradation

Progressives tend to emphasise care and fairness. Conservatives often balance all five — especially loyalty, authority and sanctity. This means a climate message framed around “global justice” might resonate with some — but alienate others. Frame it instead around “energy independence,” “local pride,” or “protecting future generations” and you might open new doors. Karimi-Malekabadi et al. (2024) found climate goals were often shared — but justified by different values.

Example: the Net Zero voter dilemma

Marcus values hard work and national stability. He’s unsure who to vote for.

He hears one party say: “Fight for climate justice.” He switches off.

Another says: “Secure Britain’s energy future.” He leans in.

Same policy. Different narrative. Different values activated. Research shows that climate concern is high across demographics, but climate action is increasingly perceived as left-coded. When campaigns speak only one moral language, they limit their reach.

What changemakers should do differently

To engage hearts, heads and hands:

- Heart (Values): Use moral foundations that reflect their worldview

- Head (Identity): Affirm roles people already value (e.g. parent, worker, citizen)

- Hands (Actions): Offer behaviours that reinforce that identity, visibly and socially

What changemakers can do differently

To build real momentum — for climate, health, inequality or anything else — we need to engage all three cogs:

|

Cog |

Function |

Campaign

Strategy |

|

Heart (Values) |

Provide

emotional and moral direction |

Frame

campaigns using multiple moral foundations (not just fairness) |

|

Head (Identity) |

Translate

values into behaviour |

Affirm

relatable roles: parent, neighbour, patriot, worker |

|

Hands (Action) |

Make

identity tangible and socially reinforced |

Offer visible,

doable, socially supported behaviours |

Bringing it all together: why Heart, Head and Hands must move as one

We’ve spent years trying to spin the outer cog — more recycling, fewer flights, plant-based diets and there is evidence that this has a positive impact. As De Meyer (2023) puts it: “Action creates agency.” People change not just by believing — but by doing and then seeing themselves differently. However, without engaging identity and values, behaviour change often stalls or snaps back. When campaigns:

- recognise people’s core values (even when different from our own)

- affirm their identity (rather than attack it)

- offer actions that reinforce that identity

…change becomes something people own, not something they resist.

People don’t want to be pushed, they want to act in ways that reflect who they already are, or who they aspire to be. Meet them where they are — and turn all the cogs together.

Suggested reading & references

- Bamberg, S., Rees, J.H., & Seebauer, S. (2015). Collective climate action: Determinants of participation intention in community-based pro-environmental initiatives.

- Bem, D.J. (1972). Self-perception theory.

- De Meyer, K. (2023). Actions drive beliefs: On the stories of human agency that can beat climate doomism.

- Haidt, J. & Graham, J. (2009). The moral foundations of politics: Theory and evidence.

- Karimi-Malekabadi et al. (2024). A value-based topography of climate change beliefs and behaviors.

- Krause, N. M., & Scheufele, D. A. (2025). Our changing information ecosystem and science communication.

- Oxford University (2022). Climate change has become politicised: European public opinion.

- Sparks, P., & Shepherd, R. (2020). The impact of identity on climate beliefs and behaviours.

- Stets, J. E., & Burke, P. J. (2000). Identity Theory and Social Identity Theory.

- Tóth-Király, I., et al. (2023). Feedback loops between beliefs and personal goal achievement.

- van der Werff, E., Steg, L., & Keizer, K. (2013). The value of environmental self-identity.

Member discussion